It’s meant for all of you, our customers, suppliers, partners, or colleagues of Coppernic. Those of you who have had the chance to meet Jacky Lecuivre, the founder of our company.

For those of you who have crossed paths with him and were affected by the encounter.

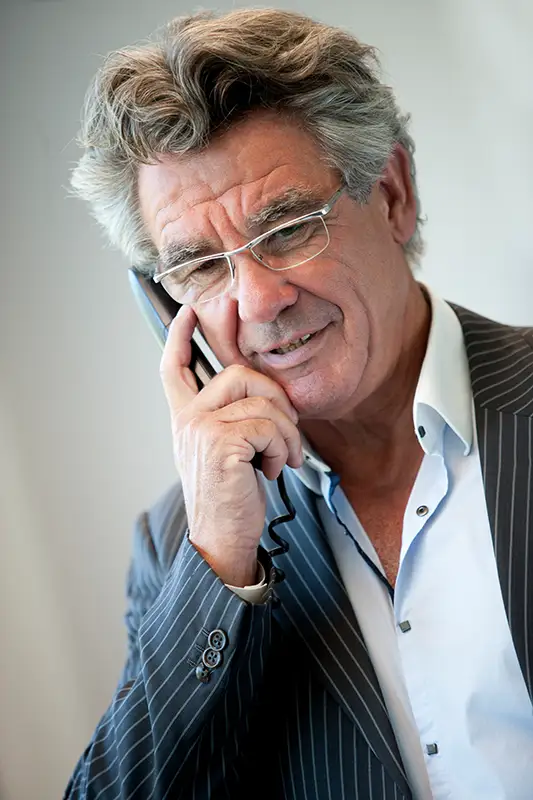

For those of you who were moved by his charisma, intelligence, and warm, friendly smile.

You might have seen him once or multiple times, had brief or lengthy conversations. Perhaps you thought, “I’d like to know more about him, meet him again, ask him questions, get to know him better…”

But Jacky Lecuivre left us on January 22nd.

Our shared story came to an abrupt and tragic end.

We believe that this story might interest you because you were also a part of it.

How should we tell you about it?

We were unsure.

Should it be a concise text so that as many people as possible have the chance to read it and get a broad picture of Jacky?

Or should it be a longer version that allows for details, nuances, and the smaller stories within the big one? A story based on the collection of multiple testimonials from those who closely accompanied Jacky at every stage of his career.

It’s the latter choice that we ultimately made.

This text combines elements of journalistic investigation and the work of a historian. We want to express our gratitude to his close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues who agreed to participate in our endeavor.

We, the leaders, associates, and team members of Coppernic, all know what we owe to Jacky, and our foremost duty is the duty of preserving his memory.

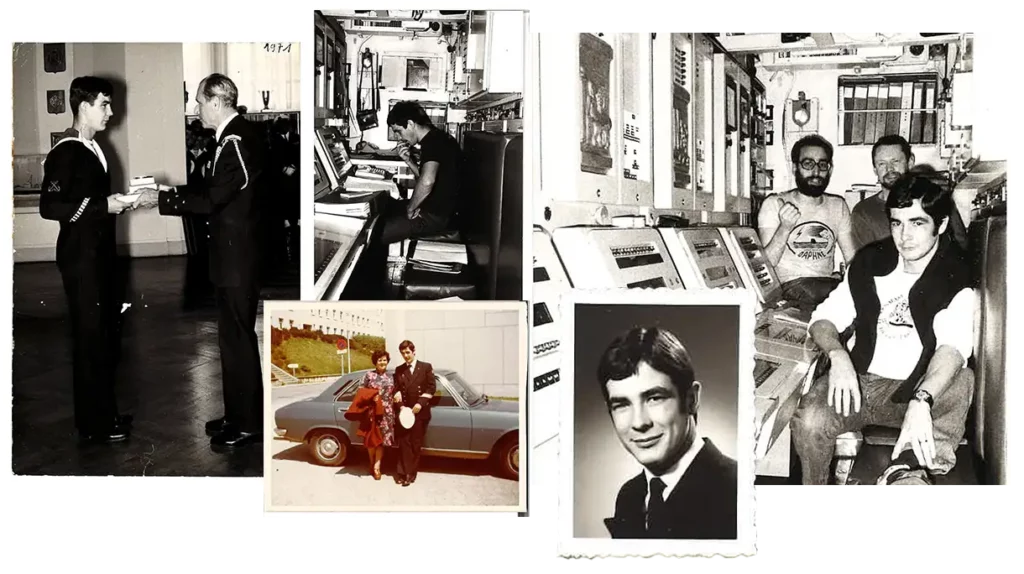

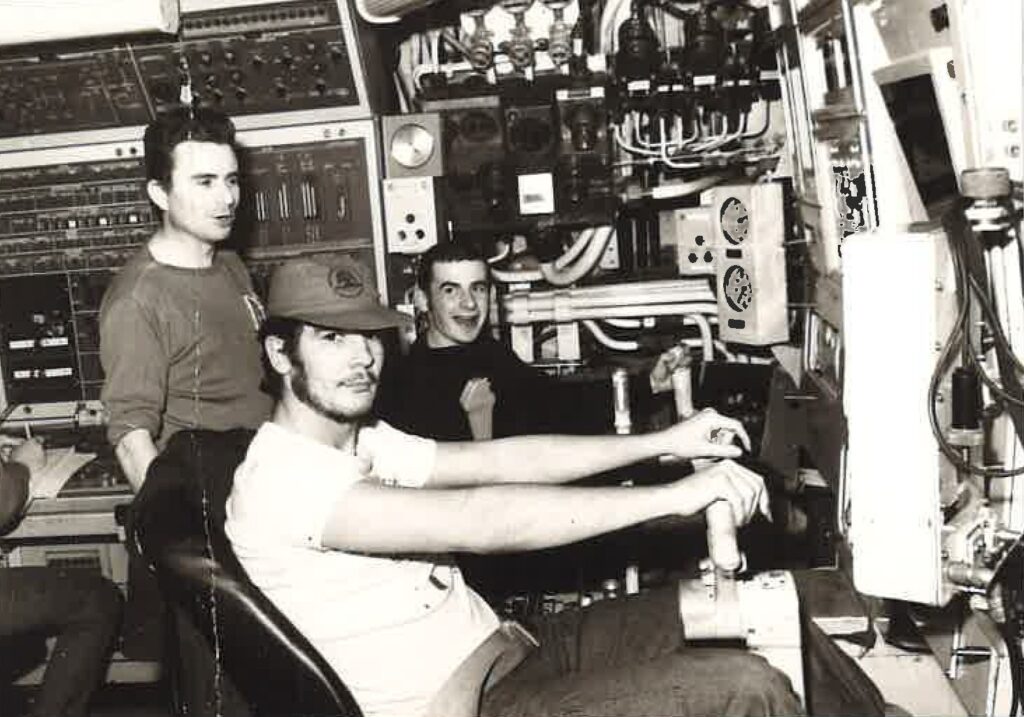

The Submariner

What kind of man was Jacky Lecuivre in his younger years? A good student, hardworking, and methodical? Yes! But he was also a go-getter, spirited, and generous, a boxer who loved challenges, fights, and adventure.

How did he reconcile all of this after graduating with a Bachelor of Science? Which career path should he choose?

And why not the French Navy?

Young Jacky loved his country but also wanted to see the world. That’s precisely what the Navy offered, along with solid technical training for which he had a natural aptitude. So, he entered the Ecole de Maistrance in Brest to become a non-commissioned officer. Non-commissioned officers, despite their name, are, in fact, skilled technicians. Jacky chose the “detection” specialty. Anything related to radars and position calculations fell under his purview.

What were the most coveted positions in this specialty? Those on one of the French Navy’s flagships, the nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) Redoutable.

Together with Jo, who would remain one of his close friends, he was responsible for the inertial navigation system. His job was to calculate the submarine’s exact position using three criteria: latitude/longitude, vertical position, and azimuth, meaning its position relative to the north. When you’re talking about launching a missile 9000 km, it’s crucial to know precisely where it’s coming from to calculate its exact destination.

The submarine’s position is a critical factor. It must be kept secret to protect it and preserve its ability to operate covertly. That’s why, during the 10 weeks of a patrol, no communication is allowed with the crew. Staying 200 meters below the surface and refraining from communication makes the SSBN almost undetectable. Even the Navy’s headquarters doesn’t know its exact location. In fact, the only person who knows it precisely is the non-commissioned officer who calculates it, Jacky!

Well, the Pacha (Captain) is also informed, of course. Apart from a few officers on board, no one else knows, and, most importantly, no one should talk about it. It’s worth noting that even decades later, despite persistent questions from his friends, Jacky has always refused to reveal the secrets of his submarine journeys.

Even in increments of 10 weeks, this underwater life added up to over two years in his first ten years of service. The periods on land were also busy. Jacky continued his studies at CNAM, stops the boxing championships (he was still the champion of Picardy), took up Triathlon, and joined the French military Marathon team.

It was on land that he could spend time with his wife Viviane and their three children. The first, Kevin, was born during a patrol, and Jacky learned about the happy event through a 20-word family telegram.

But being a non-commissioned officer is just the beginning of a career. After the first 15 years, he had to make a choice: become an officer or transition to civilian life.

One can love marching as a military officer on Bastille Day with a saber and white gloves and still not feel completely at home. Major Jacky Lecuivre never denied his working-class roots and always had a heart for the left. This caused some dissonance on board. Perhaps the later patrols on the Indomptable didn’t go as smoothly as those on the Redoutable. Long before the end of his service, he knew that he wouldn’t follow that career path.

Technology reigns supreme on a submarine. His time ashore was also dedicated to working with industrial partners on the new generation of inertial navigation systems.

The path was already set for what came next, and he was easily and naturally recruited by Mors Techniphone. This company in Puy-Sainte-Réparade, a small village near Aix-en-Provence, captured his heart. He moved there with his wife and children after a journey from Brittany in an old Renault 4L and a caravan. The caravan and the municipal campground served as the family’s home for the first two months of their new life in the South.

Mors Techniphone manufactured the radio-navigation receivers he had been responsible for before. He was the perfect fit to become the customer training manager.

The training manager must believe in the products he presents. Trainees learn better when they are convinced of the excellence of the products being presented.

In fact, the trainer extends the sales process by imparting knowledge and fostering product use. A good trainer often resembles a good salesperson. Jacky’s potential in this role was so evident that he was quickly promoted to Director of Sales.

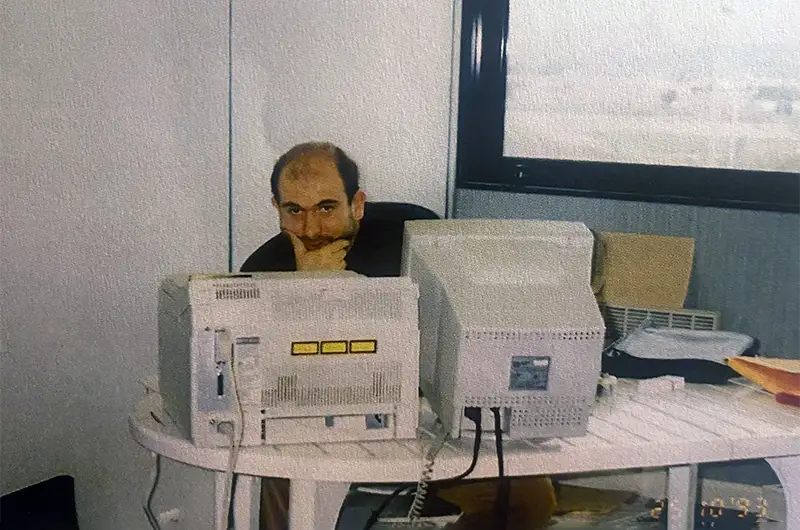

The Salesman

Maybe it was at that moment that Jacky realized he had a gift. And that this gift didn’t quite align with the submariner profession. Some of the qualities he developed were useful in sales: precision in vocabulary and procedures, infinite patience, the ability to stay alert and suddenly shift into high gear… but they didn’t define his essence.

Specialized literature distinguishes various types of salespeople: for example, the hunter versus the farmer, the former focusing on prospecting, the latter nurturing relationships, sometimes with the addition of the technically oriented expert and the consultant advisor.

Beautiful diagrams can illustrate this typology, but they can’t quite capture Jacky Lecuivre. According to those who knew him, he was a bit of both profiles. He had the fierce determination of a hunter, the attention and empathy of a farmer, the sharp product knowledge of a good technical salesperson, and the fine understanding of customer needs. He also had the gift of gab, a natural way of connecting, and the art of building instant trust.

According to numerous consistent testimonials, he was simply the best salesperson ever encountered, with seemingly limitless persuasion skills.

The products he was selling in the early 1990s were intended for industry, major defense contractors, or the automotive sector. Jacky, for instance, customized a project for Citroën.

You have to imagine that during that time, industrial inventory was still largely managed with paper records.

The forklift operator had a sheet to move parts from warehouses to the production line. A powerful computer controlled the operations, but it was blind, deaf, and depended on manually transmitted information, with all the risks of errors and delays that entailed.

What Jacky and his teams worked on ultimately became one of the major subjects of his career and a significant topic in industrial history of that era.

It can be summed up in a few words: portability, identification, interoperability.

If there was a small computer on the forklift or in the hands of its operator that communicated directly with the central computer, the problem was solved.

Except that radio links between these devices were in their infancy. Bluetooth was only invented in 1996, and WiFi in 1997.

The solution Jacky was working on involved radio communication. Furthermore, it was in a regulated sector, in the megahertz range, like FM radio, not in the gigahertz range like modern WiFi. The system proposed to Citroën’s engineers was operational, but the response time for information to pass from a device to the central computer was about fifteen seconds.

Jacky then initiated Project P5S, Project 5 Seconds, which meant he committed to improving performance by a factor of 3.

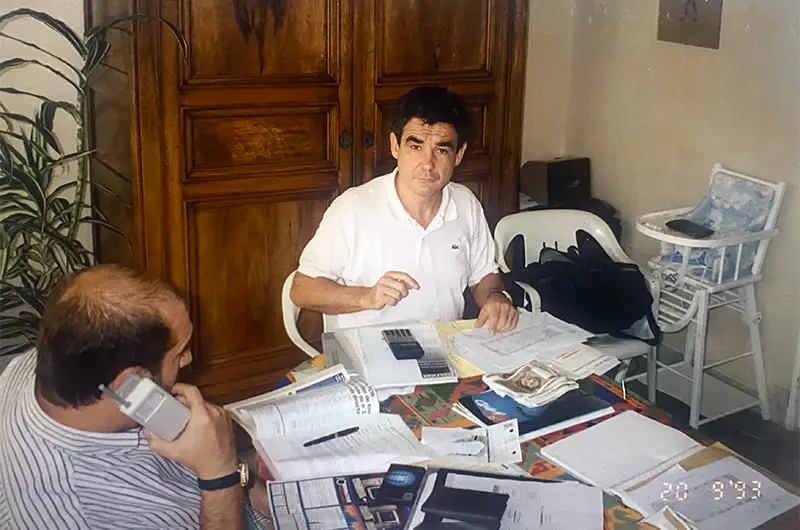

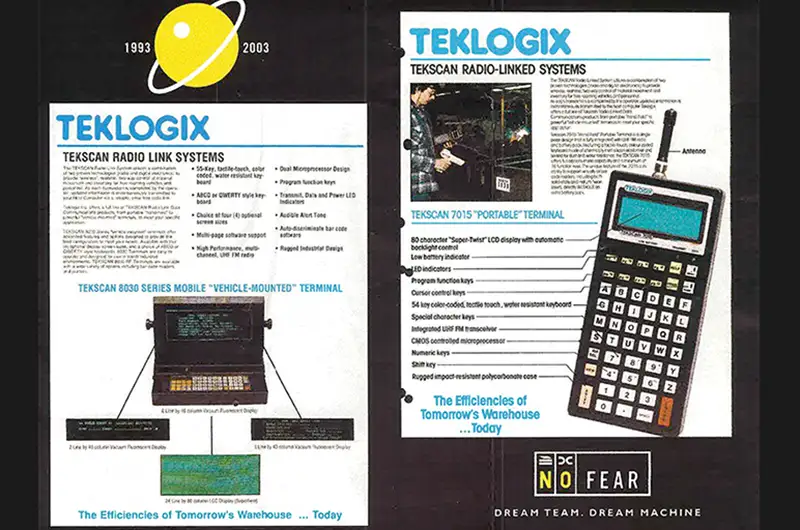

While the engineers got to work, Jacky explored various systems from around the world. One day, at a trade show in Chicago, he met the Teklogix team.

This Canadian company specialized in real-time wireless data capture had precisely the product that suited the situation. However, it wasn’t distributed in Europe. No problem, Jacky quickly convinced his employer to establish a distribution agreement with them for France.

With his allies from Ontario, Jacky was ready to return to see Citroën’s engineering team. The demonstration took place in real conditions in the immense warehouses that needed to be covered by the radio signal, while the transmission time was measured.

The verdict was in: the time had gone from 15 to 1 second.

Citroën’s engineers, lined up in their logoed white lab coats and steel-framed glasses, were surprised and incredulous. One of them, in charge of radio frequencies, went further. According to him, “It’s impossible that it covers half of the warehouse like this, that it’s so fast, there must be something, you have an antenna with a gain.” This was prohibited because emission power was regulated.

In fact, he accused them of cheating! Jacky reached for the pen in the breast pocket of the white lab coat. He unscrewed the antenna from his Teklogix device and replaced it with the pen. Another test was carried out. The coverage and response time remained the same with this improvised antenna. Citroën’s engineers, now thoroughly impressed, retracted their accusations. The pen then served as the instrument to sign a substantial contract.

The timing seemed perfect to go big. Jacky was surrounded by a high-performing team and had a technological edge with Teklogix. The potential opportunities were enormous, spanning across all industrial sectors, including retail. What’s more, there was perfect alignment between the French team led by Jacky and the Canadians, with Rod Coutts, the founder of Teklogix, at the helm.

However, Mors’ top management, Jacky’s employer, didn’t share the same vision for the market’s potential. One day, their CEO drafted a business plan on a paper napkin: “We can sell this equipment for a maximum of one to one and a half million francs. Let’s not waste any more time on it.”

The beginning of imagination is recognizing a good idea when it’s presented to you. That’s what set Jacky apart from his hierarchy. That’s what brought Jacky and Rod Coutts, the founder of Teklogix, together. These two were clearly meant to collaborate.

Jacky was ready to part ways with Mors and proposed creating Teklogix’s French subsidiary. Rod Coutts was all for it, but he was tied by an exclusivity agreement, and Jacky’s employer didn’t want to let go of either their exclusive product or their exceptionally talented sales director. The bidding war escalated, relations grew strained, and negotiations reached an impasse.

That’s when Rod Coutts proposed that he and Jacky seal the deal with a simple handshake. Based solely on that handshake, and without any other guarantees, Jacky and his two main team members, Pascal and Guy-Franck, simultaneously resigned.

The legal complications took a few months to resolve, but the foundation was built on Jacky’s preferred principle: trust. In the meantime, the three comrades dreamed big and honed their skills. Rod Coutts provided for their needs, and one day, he even handed them a briefcase full of 500-franc bills!

In the end, he managed to break the impasse. Jacky became the Managing Director of Teklogix France, and the success story could finally begin.

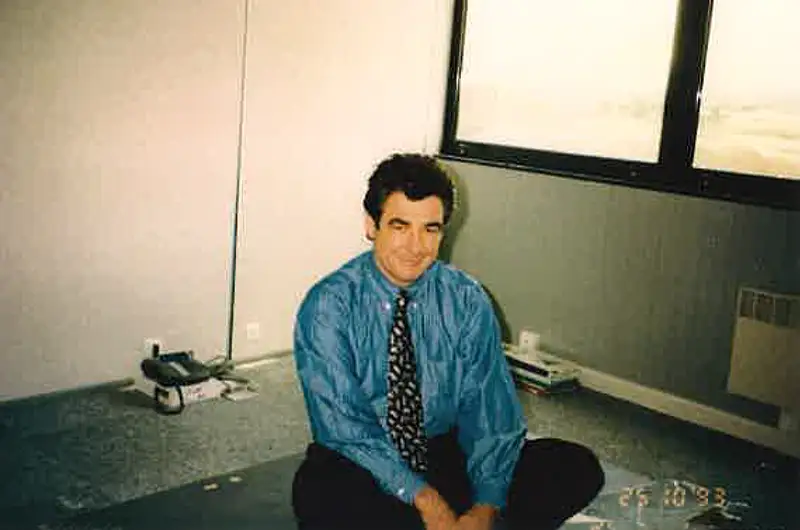

The Manager

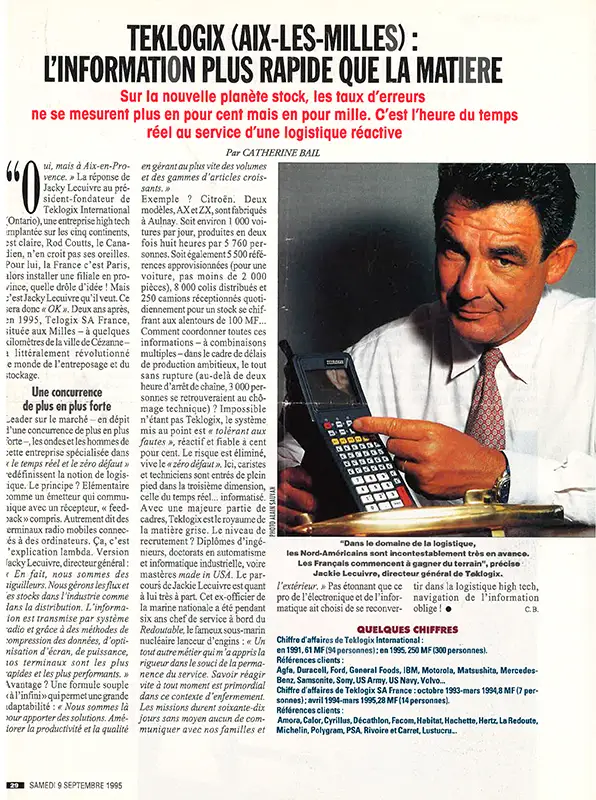

At that time, Teklogix had a few hundred employees, but it had grand ambitions. Subsidiaries were established almost simultaneously in the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Benelux countries, and beyond.

A global market was emerging for radio transmission-based data identification and processing terminals. Teklogix excelled at interfacing portable terminals with large IBM computers better than anyone else. The market was highly competitive, featuring historic companies like Symbol and LXE, which would later be acquired by giants like Motorola and Honeywell. Still, Teklogix France’s team was the most aggressive, knowledgeable, and motivated.

Successes started piling up quickly. The potential market, estimated by some to be at most one and a half million, exploded within the first few months, reaching tens of millions in revenue. The team expanded, and the dynamics with it. The French market proved to be the most profitable and dynamic in all of Europe, leaving Rod Coutts deeply impressed.

Was there a Jacky method? And what was his secret?

Sure, Jacky was an excellent salesperson, with unwavering determination, in-depth knowledge of his projects, and a natural talent for being a showman. However, he couldn’t be everywhere at once. His success was primarily attributed to a more crucial factor: Jacky was first and foremost a leader of men and women. His ability to unite his teams toward a common goal was his most significant contribution.

His military experience had left him averse to top-down management. All of his former colleagues and collaborators attest to this: he was never authoritarian or forceful. When asked about his main managerial quality, one response almost always stood out: “He’s someone who listens, and more importantly, he’s someone who knows people, takes a genuine interest in them, understands their expectations, and brings out the best in them.”

Add an exceptional memory to the mix, and you have another part of his secret. When he inquired about someone’s youngest child, it wasn’t just a routine gesture; it was genuine curiosity. During the next meeting a month later, he remembered the child’s name, age, and even their childhood illness. He also recalled their projects, temperament, and preferences. This knowledge allowed him to offer each individual the right position within the organization, tailored to their skills and growth potential. According to Lydia, “He has the gift of spotting talents and nurturing them.”

While he expected others to share his passion, determination, and hard work, he understood that this could only happen in an optimal environment where everyone felt at ease and where hierarchy existed to support rather than control. When a new person joined the organization, they had to immediately sense that they were “welcome on board.” Marc remembers Jacky saying, “We’re going to have a great time together” during the contract signing. Can you imagine any other boss saying that? In any case, the contrast with his previous employer was striking.

Perhaps Jacky could have written books on compassionate management, “care,” or “nudging” long before they became trendy. The truth is, he was simply following his temperament and instincts. He viewed a company as a whole, where everyone had a place and contributed to the team’s success. And, as always, he remained attentive to every detail and every person.

From a very practical perspective, he refused to reserve performance bonuses solely for salespeople. Engineers and employees in shipping or accounting also deserved performance-based bonuses. Regarding compensation, were Teklogix employees well-paid? Not more than the market average. Probably less than employees at a large company in the Paris region. For Frédéric, that wasn’t the point. “The whole ecosystem envies us.” Teklogix was the team that won bids, piled up successes, and celebrated them exuberantly. “Work like dogs, Party like Animals.”

To illustrate the unique atmosphere that pervaded the company, an analogy may help. Jacky ultimately found the sport that suited him best—not boxing but rugby.

Unfortunately, this encounter, initiated by Pascal and recounted by Thierry, occurred relatively late. Jacky was no longer a young man, so he couldn’t pursue a career as a scrum-half or a flanker.

However, both his sons would excel in rugby at a high level. Jacky didn’t just watch from the stands; he became involved with the Aix-en-Provence club (PARC), serving as one of its vice-presidents for a long time before presiding over the Aix University Club Rugby (AUCR).

Rugby was a true revelation for Jacky.

It was the quintessential team sport, characterized by physical engagement that could sometimes be brutal while maintaining the spirit of a gentleman’s game. Rugby brought together people from all walks of life, nationalities, backgrounds, and horizons. A player might barely touch the ball throughout an entire match and still be a key contributor.

The player who jumped the highest in the lineout did so with the support of his teammates who lifted and propelled him. The very essence of this sport, where one individual was nothing without the other 14, served as a real source of inspiration for Jacky, and he applied these principles throughout his professional career.

Jacky kept all these metaphors in mind constantly. In his company, he played the roles of both the player and the coach, with a touch of the captain’s leadership. Of course, he was always the first to initiate the post-match “third half.”

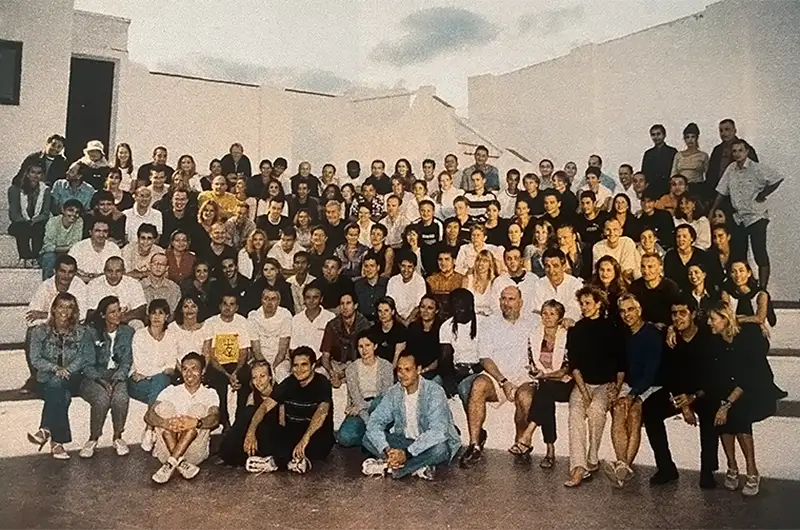

The Teklogix France parties became renowned throughout the company.

As Jacky took on more responsibilities within the organization, these legendary gatherings began to spread worldwide. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Teklogix France was founded in 1993 by Jacky, along with Pascal, Guy-Franck, and a few others. Within a few years, the subsidiary became the top-performing one in Europe, generating revenue surpassing that of all the European subsidiaries combined. The Teklogix Group had now become a global brand, present on every continent.

Rod Coutts, the president and founder of the company, was seen as an ideal boss and even a mentor to Jacky. Jacky admired his intelligence, simplicity, and unwavering commitment to his values. His humility set him apart from his peers, the arrogant tech tycoons.

However, this passionate engineer didn’t feel suited to the role of a CEO. He gradually organized his retirement and eventually sold his company in 2000.

The VP World

If Teklogix, operating in the B2B sector, was known primarily within technological and industrial circles, the company that acquired it was a global star.

Psion was the brainchild of David Potter, an Englishman and former student of Trinity College, Cambridge, with a doctorate in mathematical physics. He was something of a tech guru. The name of his company, founded in 1980, was an acronym for “Potter Scientific Instrument Or Nothing,” which gives you an initial insight into his personality.

Psion made its name with a flight simulator for the famous Sinclair ZX81. The company was also responsible for creating the very first office suite in 1983, and, most notably, it invented the PDA (personal digital assistant) in 1984. The PDA revolutionized the way businessmen managed their schedules, contacts, and basic word processing and calculation tasks, replacing both the Casio calculator and the Filofax agenda.

The idea was undeniably brilliant, and it enjoyed immense commercial success. David Potter’s series of brilliant insights placed him in the tech hall of fame, much like Steve Jobs. Every word he uttered seemed like an oracle. While the 1980s had solidified his reputation, the 1990s were less kind to him. He didn’t anticipate the convergence of PDAs with telephony, downplayed the future of the Internet, and didn’t believe in home computing for the general public. Others had a clearer vision.

By the late 1990s, his PDAs had gone from being the world’s top choice to fifth place. What’s more, the very concept of PDAs was under scrutiny, and the market was collapsing. Phones like the Blackberry were now taking over the niche.

The acquisition of Teklogix was a way for Psion to diversify its business into the B2B sector, which it had been less involved in previously. However, unlike typical acquisitions, this absorption did not lead to a reorganization of Teklogix’s organizational chart. The key executives either remained in place or saw their responsibilities expand.

For $368 million USD, David Potter acquired a well-functioning tool. This reinforcement turned out to be even more critical than initially planned. In the years following the acquisition, Psion’s other activities inevitably came to a halt. Psion was quite literally saved by Teklogix.

Jacky Lecuivre continued his ascent within the new entity, Psion-Teklogix. He successively held positions as Director of France, Director of European Sales, Director of EMEA, and VP of Global Sales.

The dynamics that characterized the early days of Teklogix France continued and grew stronger. The work environment was characterized by a strong sense of cohesion among employees. As Jacky took on international responsibilities, he disseminated his management methods.

Subsidiaries in the UK, Germany, and Italy realized that they were part of the same team, and synergies were created. Events were held every year in different countries, whether it was a Christmas party or a kick-off party, always with the same motto: “Work like dogs, Party like Animals!” Participants came from across the EMEA region. These events weren’t exclusive to the management team.

For example, you might encounter a driver or a cleaning staff member who had come all the way from South Africa to Marseille, a bit bewildered at first but vigorously invited to join in the festive evening.

Regardless of their role, everyone should feel like they were an integral part of the team. Valérie, who had been pulled from her documentation department, had the opportunity to participate in trade shows in Amsterdam and seminars in Tunisia. Lydia and Blandine accompanied him to Canada to meet the Psion HR teams, and he took the time to drive them for hours to show them Niagara Falls. His responsibilities didn’t change him; his availability was immense, and his energy seemed boundless.

He was also an indefatigable globe-trotter, a record holder for miles traveled on transatlantic flights, and a record holder for losing his luggage. And, he was the champion of self-deprecation, delighting his audience with tales of his mishaps at the coffee machine.

The CEO

This phenomenon eventually intrigues David Potter, the all-powerful Chairman of the Board at Psion: “What if he’s the CEO I need?”. When it comes to CEOs, David Potter tends to change them often in his quest for the ultimate formula. The concept of scalability isn’t yet trendy in tech, but it’s been clear for a long time that the true sign of success is monetary, and shareholders preside over all strategic decisions based on motivations far removed from Jacky’s very pragmatic aspirations. David Potter is very wealthy; he wants to become extremely rich. Is Jacky capable of achieving that for him?

This moment marks a crucial turning point in Jacky Lecuivre’s career. In 2008, this little Frenchy (1m87 tall in fact), born in Soissons and residing in the heart of the Provençal garrigue in Puy-Sainte-Réparade, was appointed CEO of a company headquartered in London, with its main production site in Mississauga, Canada, and a global presence.

Jacky continued what he had been doing since the late 1980s. He offered his industrial and major governmental clients cutting-edge terminals that were perfectly suited and customized to their specific business needs. New product lines were launched with significant success. The Workabout Pro was a massive hit, and engineers based in Aix-en-Provence were working on new products that integrated RFID, facial recognition, and biometric fingerprint scanning. This little corner of Provence was beginning to resemble Silicon Valley. However, Jacky cared just as much, if not more, about the motivation of his teams and meeting his customers’ needs as he did about the next technological disruption.

Sales figures were good, and operational margins were healthy.

Jacky developed a new habit. He made regular trips to London. At the airport, a chauffeur-driven German sedan would take him to the Psion headquarters. The half-day was spent reporting to the meticulous board of shareholders.

In English-speaking countries, CEO is often translated into French as PDG (Président-Directeur Général). However, in reality, the “P” for President is absent from the English acronym. The “E” for execution is the operative element.

Rod Coutts, the founder of Teklogix, once gave a lecture in which he shared the essence of his entrepreneurial experience. According to him, there are three legs that support a company, much like a milkman’s stool.

The technical and operational direction, the sales and marketing direction, and the administrative and financial direction. Each contributes to the balance of the milk stool: the first says what can be done, the second what should be done, and the third what should not be done. If one of these components no longer plays its role or exerts too much influence over the other two, peril is in the house.

Perhaps, on his flight back from London, Jacky sometimes wondered if these financiers in their Savile Row suits, who had never seen a customer and only thought about the money that money should make, were the right people to be at the top of the entrepreneurial edifice.

If he had doubts, it didn’t stop him from moving forward. A new product was in the works: the IKÔN. It was described as a “barcode reader, integrated scanner, camera, operable under three operating systems, incorporating voice communication options, GPS location, Wi-Fi, GSM/GPRS, and Bluetooth connectivity.”

It was also designed to withstand falls, heat, dust, and rain, known as “ruggedized” terminals capable of surviving in industrial environments. It represented the culmination of Psion Teklogix’s expertise.

This launch coincided with another event: Teklogix’s 40th anniversary in October 2007.

Invitations were sent out, and over 600 guests, including spouses, gathered in Paris at prestigious venues for 40 hours of show, business, and celebration. David Potter and Rod Coutts were part of the journey. The conferences took place at the Carrousel du Louvre, and the closing evening was held at the Pavillon d’Armenonville.

The operation was a tremendous success, largely thanks to Fanny, Jacky’s daughter, whose company was the mastermind behind the festivities. Clients from around the world were impressed. During the closing evening, the atmosphere was more like a rock concert than a symposium.

Some remember seeing Jacky on stage, his tie wrapped around his head like a pirate, belting out “Highway to Hell” with the musicians and clients from all over the world.

This moment was undoubtedly a peak in his career. And after the peaks, there is the descent.

In addition to the festivities, a board meeting was scheduled. David Potter outlined his new objectives to Jacky.

The results were good, and the stock price was rising. “Perfect! Let’s make it rise even more by laying off a hundred people,” Potter said. And David Potter confirmed to Jacky that the “E” in CEO stands for execution. Between the two of them, nothing was going well, and a rupture seemed inevitable.

However, Jacky believed he still had a card to play. David Potter hoped to sell Psion. Jacky presented him with a potential significant buyer: Honeywell, a global conglomerate with a wide range of interests, from electronics to aerospace. This “World company” was considering buying Psion. A meeting was arranged by Jacky on Wall Street.

Honeywell’s CEO at the time, in jeans and a bomber jacket, met the British businessman in his double-breasted suit. He laid out a check with such a large amount that it came with a confidentiality clause. Jacky was elated. This check represented for him the opportunity to change the course of the board, to put an end to this cost-cutting strategy.

Unfortunately, Potter rejected the offer. He found the price too low. Jacky was devastated. He believed less than ever in his President’s foresight. Wasn’t it Potter who had declared that Steve Jobs was making a colossal mistake by marketing the iPhone? “He’ll realize he should stop when he’s sold 10,000!” No comment…

Potter’s verdict was as follows: to improve Psion’s selling price, they needed to make a nice gift package and find a new buyer by next year. All they needed to do was cut a quarter of the workforce, stop customization, and shut down certain services like the R&D division in Aix-en-Provence… This time, it was too much. Jacky refused to cut 300 jobs to enrich a few shareholders. He stepped down from his CEO position, after barely two years, even if that constituted a record of longevity at the time.

As for David Potter, he finally exited this story when he managed to sell Psion in 2012 to Motorola for $250 million USD, which was significantly less than the offer received four years earlier. The following year, the Psion brand disappeared.

Potter Scientific Instruments Or Nothing?

In the end, it was Nothing.

The Founder

Jacky Lecuivre, the CEO of Psion, isn’t someone you can just let go with a nod. His excellent results, his standing within the company, and his reputation in the market make it impossible. But what role do you give him after he’s held the top position?

Ultimately, he goes back to his previous position as VP in charge of global sales. It’s a compromise, both for Jacky and for Psion. Jacky is getting ready to bounce back and needs some time. Psion especially doesn’t want him to join the competition or become an adversary. He could easily settle into the twilight of his career, “slippers under the radiator,” until a well-deserved retirement, but that doesn’t factor in his insatiable appetite and his constant quest for new challenges.

A solution eventually emerges. Jacky had assembled a small group of engineers within Psion, at the Aix-en-Provence site: experts in wireless communication systems and data capture technologies, including biometrics, imaging, laser scanners, RFID, smart cards, OCR, etc. The goal of this group was to integrate these technologies into portable terminals, to design, develop, and provide products tailored to mobile workers in various market sectors: public transportation, access control, meter reading, secure document authentication, personal identification, and law enforcement.

Psion’s board of directors decided to dismantle this group. But why not reconstitute it as an independent company?

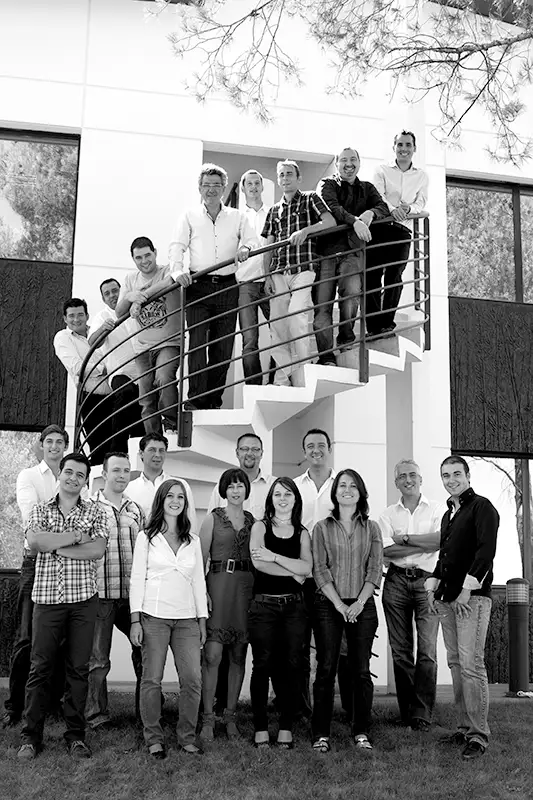

Negotiations began for a partnership. The agreement reached stipulated Jacky’s departure, along with that of 10 key individuals who would both constitute the driving force of the new company and be its founding shareholders.

Coppernic – the name coined by Kevin Lecuivre – was launched at the end of 2008.

Jacky could count on his partners: Alain, Benoist, Blandine, Christophe, Fabien, Gilles, Kevin, Marc, Philippe, and Philippe. 10 + 1, it looks more like a soccer team than a rugby team, but that didn’t stop them from feeling as strong as the All Blacks.

He also benefited from Psion’s endorsement and guarantee for a €450,000 loan taken by the young company in exchange for a 3-year exclusivity clause.

The small team got to work. They could retain some historical clients and continued to use Psion terminals for their integrations.

In the first year, results were there, and a profit was made. Coppernic found its niche: customization, developing new uses, staying at the cutting edge. Their clients were government agencies, distribution network managers, transport companies, and industrial enterprises.

Over the years, Coppernic moved away from Psion’s hardware and eventually built its own terminals.

Even though the B2B market isn’t as hungry for innovation as the consumer market, Coppernic launched innovative products like its C-One terminal, the market’s first compact device without a keyboard, with the same integration capabilities as the Workabout Pro. Jacky dubbed it the “Swiss Army knife of mobility.” He loved reminding Coppernic’s engineers that their job was to develop the finest blades for that knife.

One of the possibilities offered by these technologies was biometrics. A device barely larger than a smartphone could capture fingerprints and photograph a person, ensuring their identification and integration into a database. The prospects were numerous. There was one that no one had thought of, involving democracy.

In 2012, following a trade show in Amsterdam, Coppernic secured a contract with Ghana, providing 33,500 terminals capable of creating certified electoral lists and instantly verifying voters’ identities through their fingerprints. The terminal scanned the barcode on the voter list, checked the fingerprint, and displayed the verdict. Green or red light: it was instantaneous. This process allowed the publication of Ghana’s election results the day after the vote, with no disputes or doubts.

Jacky was thrilled, realizing such a project, for such a cause, in an African country, a continent he loved and admired so much!

The same type of equipment was also used for border control in Europe. This time, Coppernic’s rallying cry was technological sovereignty, data security, and compliance with GDPR legislation. These were not issues that could be left to American or Chinese companies that might have backdoors allowing access to the population’s data. Jacky was in a very bad mood when, despite these concerns, French companies or sponsors neglected to turn to excellent national manufacturers.

Coppernic was now on a roll. They had proven the validity of their business model. Amid market uncertainties and occasional bumps, they continued their journey and explored new territories. For Jacky, it was time for operational retirement, as the next generation took charge of the company. Nevertheless, his thirst for success and his fondness for the sales profession he loved so much led him to tackle new challenges that required the kind of tenacity only he possessed: working with major government ministries (MINARM and MININT), and he succeeded brilliantly in 2022.

The Successors

Since 2013, Kevin Lecuivre has been the Managing Director of Coppernic.

He’s seen his father work for as long as he can remember, and he’s been working alongside him for almost as long. It happened naturally, without any predetermined plan.

As for his education, Kevin attended a good business school and also played rugby in a competitive league (that counts for a lot!). In terms of experience, he joined Psion Teklogix as a mere intern back in 2002. At that time, a new terminal had just been released, a result of R&D collaboration between Teklogix and Psion, called the Netpad. No one really knew how to sell this equipment, as it didn’t fit into either company’s product range or their existing customer base. Surprisingly, it was Kevin, the intern, who made the first sales and earned his place in the company.

Jacky was particularly adamant about not showing any favoritism or granting special privileges to his son. How could Kevin receive special treatment when he was learning the ropes on his own, even spending time in South Africa in 1999 and 2000? By 2005/2006, he was named the top global salesperson for the company, thanks to major projects won with EDF and SNCF. Success doesn’t wait for age, especially when he repeated this feat in 2007 and 2008.

On the other hand, Fanny started her own event management company in Paris. Her father indeed gave her a boost by allowing her to participate in the competition for the grand event marking the 40th anniversary of Psion Teklogix. If he did so, he took two precautions. He didn’t participate in the vote to select the chosen agency, and he asked each competition participant to anonymize their proposal. Fanny won against more experienced and likely more demanding competitors.

A few years later, she joined the new Coppernic organization in Aix-en-Provence as the head of marketing and communications.

Only Pierre-Alexandre, Viviane and Jacky’s youngest and 3rd child, escaped the Coppernic trap and is now pursuing an entrepreneurial career in van fitting…

Each of the founding associate members deserves recognition for their commitment to the collective project, but one of them holds a special place as the Technical Director, ensuring the technological excellence of the hardware and software developed. Marc, loyal from the Psion era, is now the Managing Director.

One person isn’t among the original “top ten” but joined more recently. His name is Rob, and he’s Canadian. He only joined Coppernic in 2021 but had worked for over 20 years at Teklogix and Psion Teklogix, both in Canada and France.

His late arrival is reminiscent of a return to his roots. His presence demonstrates the continuity between Teklogix and Coppernic. The same spirit prevails in both entities.

That spirit is Jacky's...

It’s the spirit of Jacky, who walks the halls of Coppernic as he once navigated the corridors of submarines. It’s the spirit of Jacky, who leans over the shoulder of developers and electronics experts, who keeps questioning technical solutions, who whispers his arguments and punchlines in the salesperson’s ear, who protests and rages against biased markets and the privileged elite. It’s the spirit of Jacky, the eternal Don Quixote in the winds of the City, the top salesperson around the world, a friend to people everywhere. His lost suitcases, somewhere beyond the oceans, on a luggage carousel, keep going around and around…

This story was told by Fanny, Frédéric, Guy-Franck, Jo, Kevin, Lydia, Marc, Pascal, Rob, Roger, Thierry and Valérie. A story that would never have been as beautiful or as intense without the unfailing support of his wife Viviane. Laurent was responsible for assembling these testimonials.